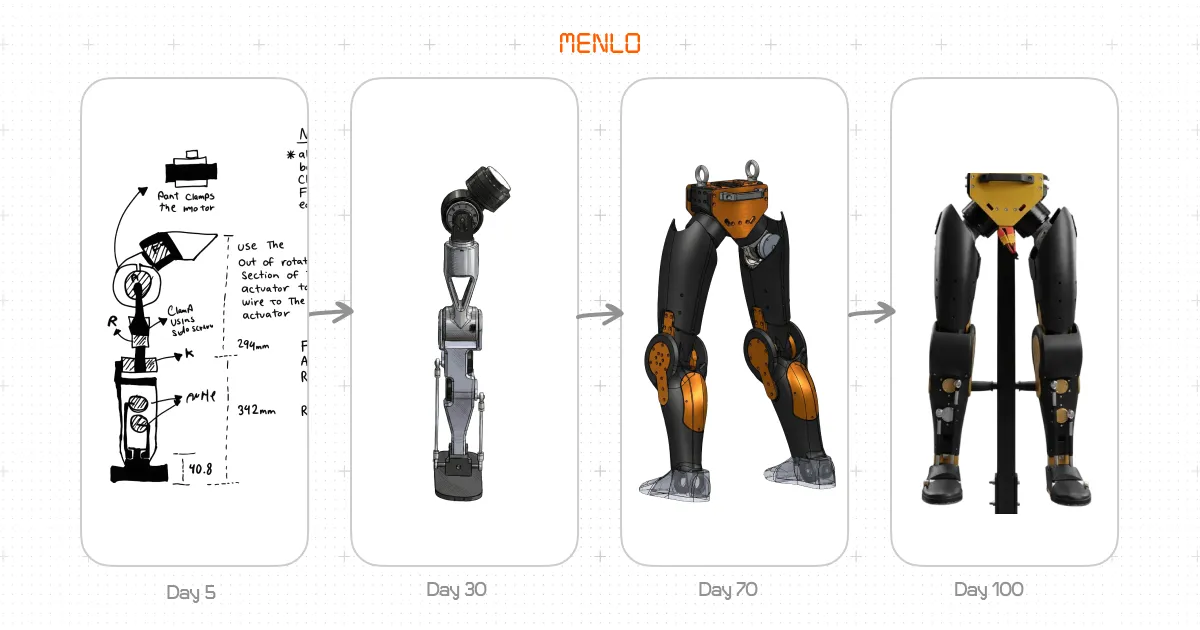

How we built humanoid legs from the ground up in 100 days

We built a full set of humanoid legs from scratch. Got them to walk. All in under 100 days. For under $30k in R&D. And we’re open sourcing everything.

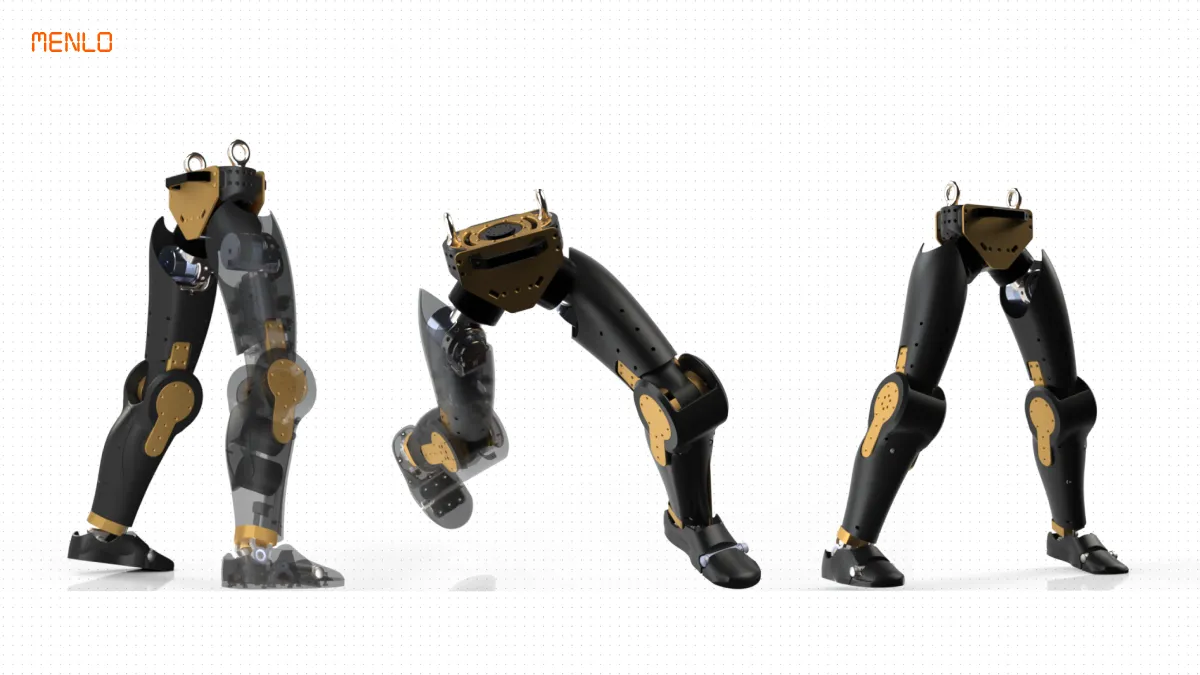

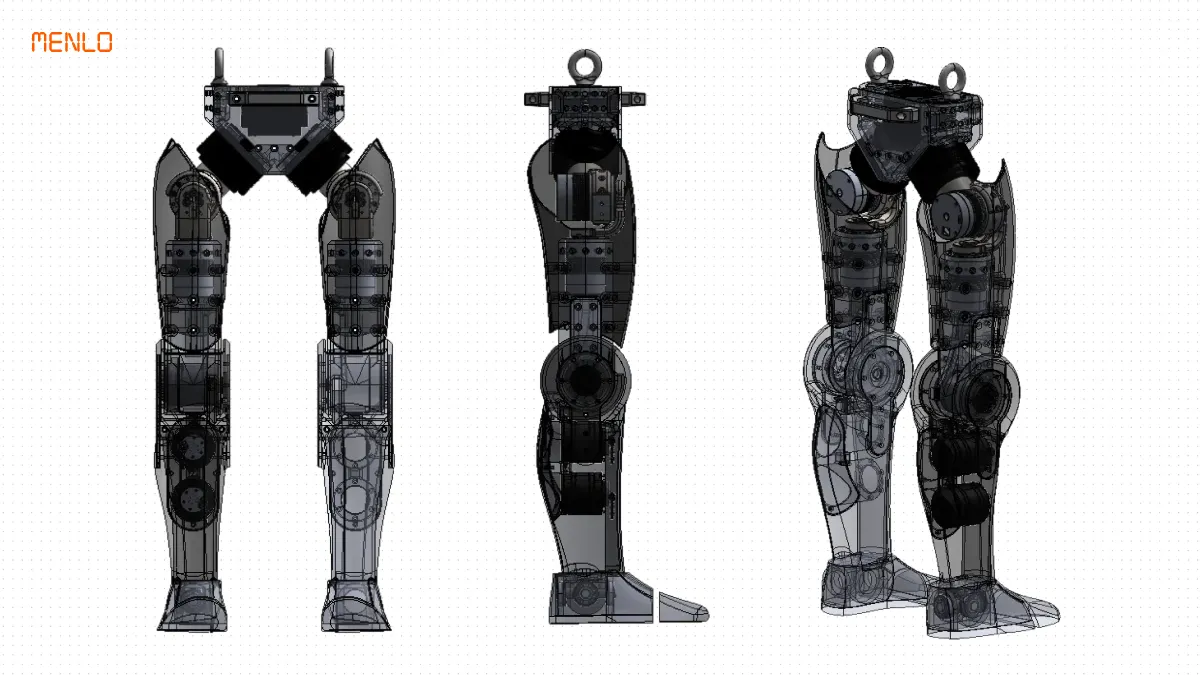

Legs are the foundation of the locomotion problem in robotics. The mechanical design of our Asimov humanoid leg is the ultimate balancing act.

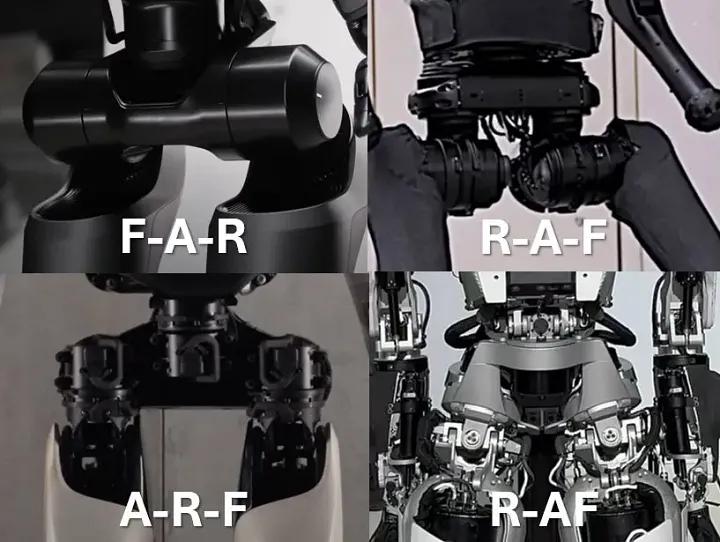

Designing for modularity

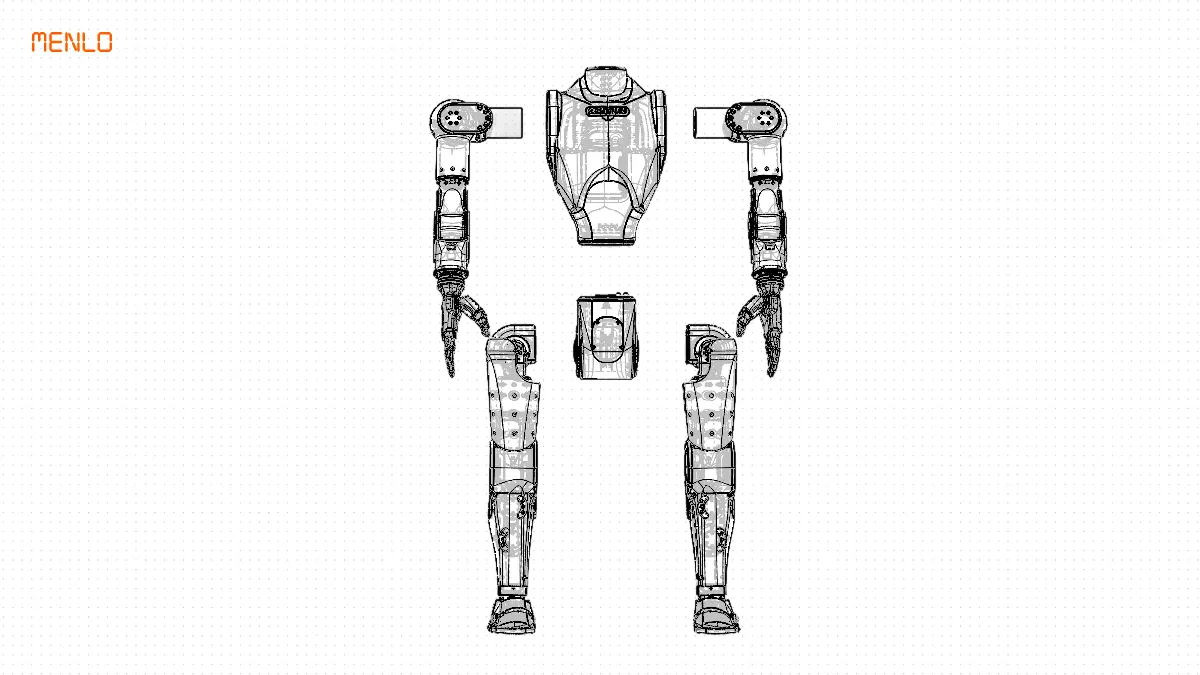

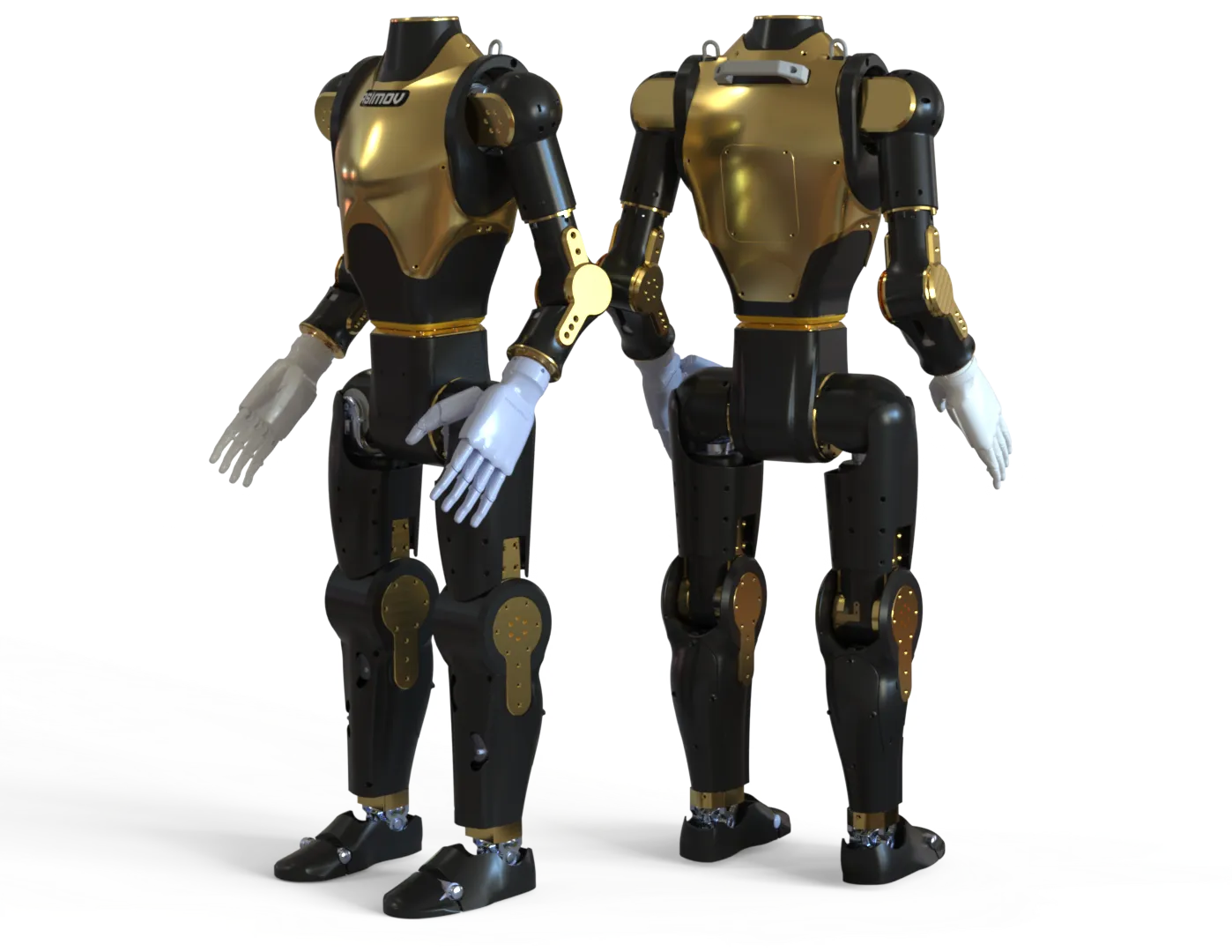

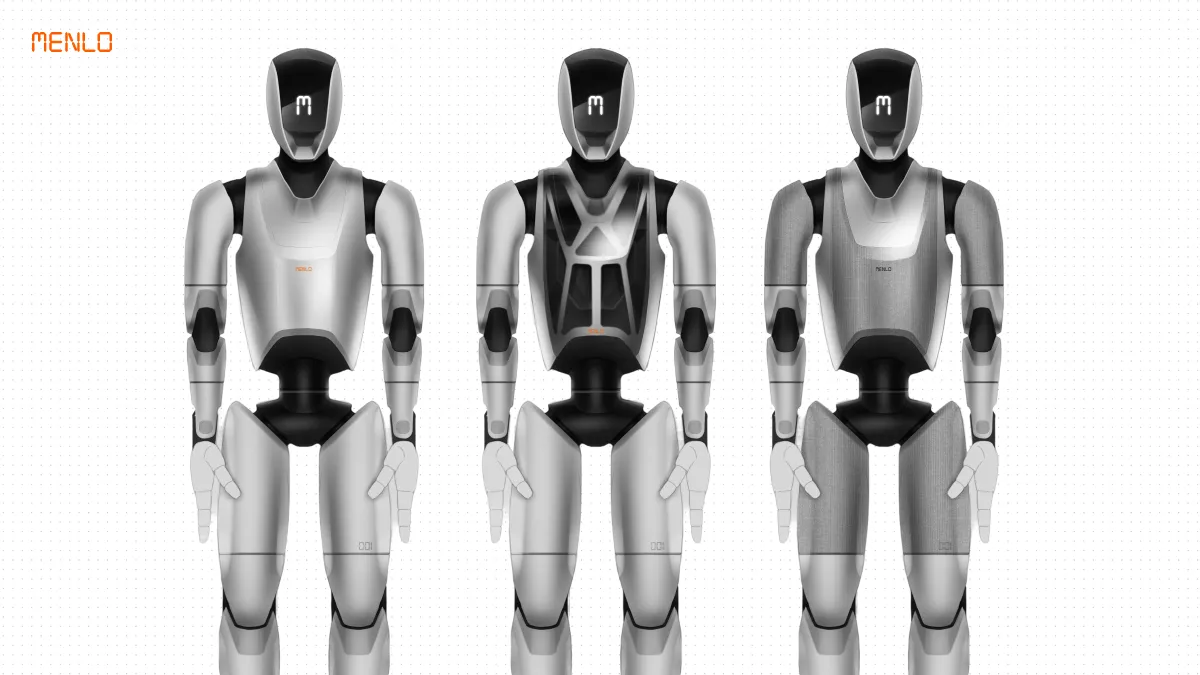

Asimov has a modular design. It consists of separate components—legs, torso, arms, head—that all snap together.

Our modular approach uses universal motor mounting fixtures, so components are swappable and the platform can be configured for different applications.

We did this for two reasons:

-

Different research labs have different priorities. Some teams want to focus on manipulation problems, others on locomotion, others on the “brain” or head unit. A modular design lets them work independently with the subsystems that matter to them.

-

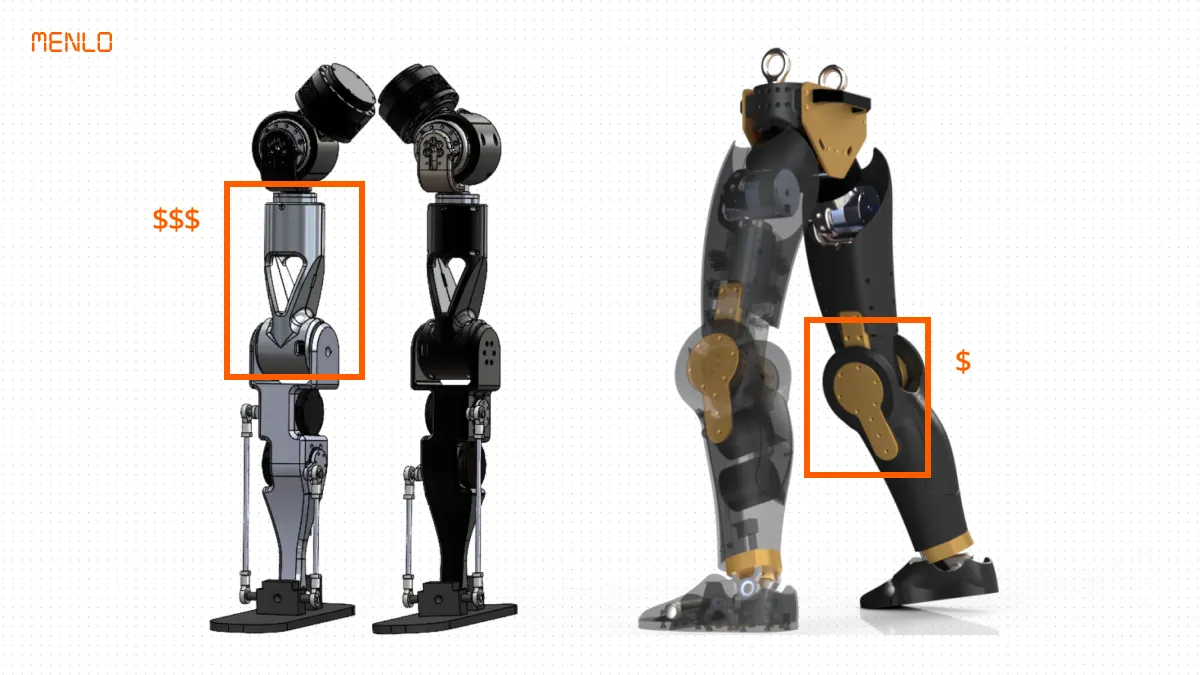

Modular designs enable assembly. Each part of the robot requires different motors. The motor that attaches an arm is completely different from what you need at the hip. Clear load paths, repeatable interfaces, and serviceable modules mean the robot can be built and maintained without specialized tooling. You shouldn’t need a PhD and a custom jig to swap out a motor.

Subscribe to the Asimov newsletter to receive notifications about upcoming posts.

Designing for decentralized manufacturing

We want anyone to be able to reproduce Asimov from anywhere in the world. For under $25k USD.

We used off-the-shelf components. For the custom parts, we chose designs that are feasible with affordable, low-volume manufacturing processes. Most structural parts are compatible with plastic Multi Jet Fusion (MJF), a 3D printing process that produces strong, functional parts without custom tooling.

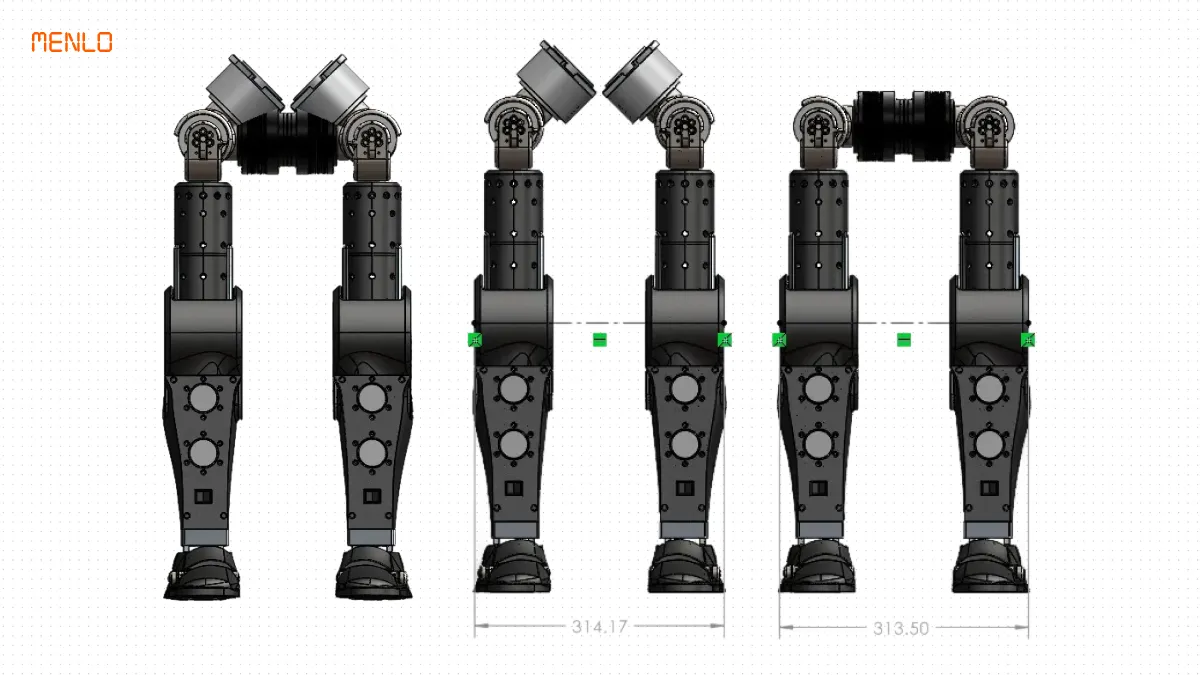

The knee plate, where stiffness and alignment are most critical, was redesigned several times. The initial design was a 2-part 3D design that required more complex tool paths, multiple setup changes, longer machine time, greater material removal, and additional assembly steps. We simplified the CNC machining requirement and turned the knee component into a plate instead.

The geometries are also amenable to alternatives like casting or traditional 3D printing, so teams without access to industrial MJF can still build the robot.

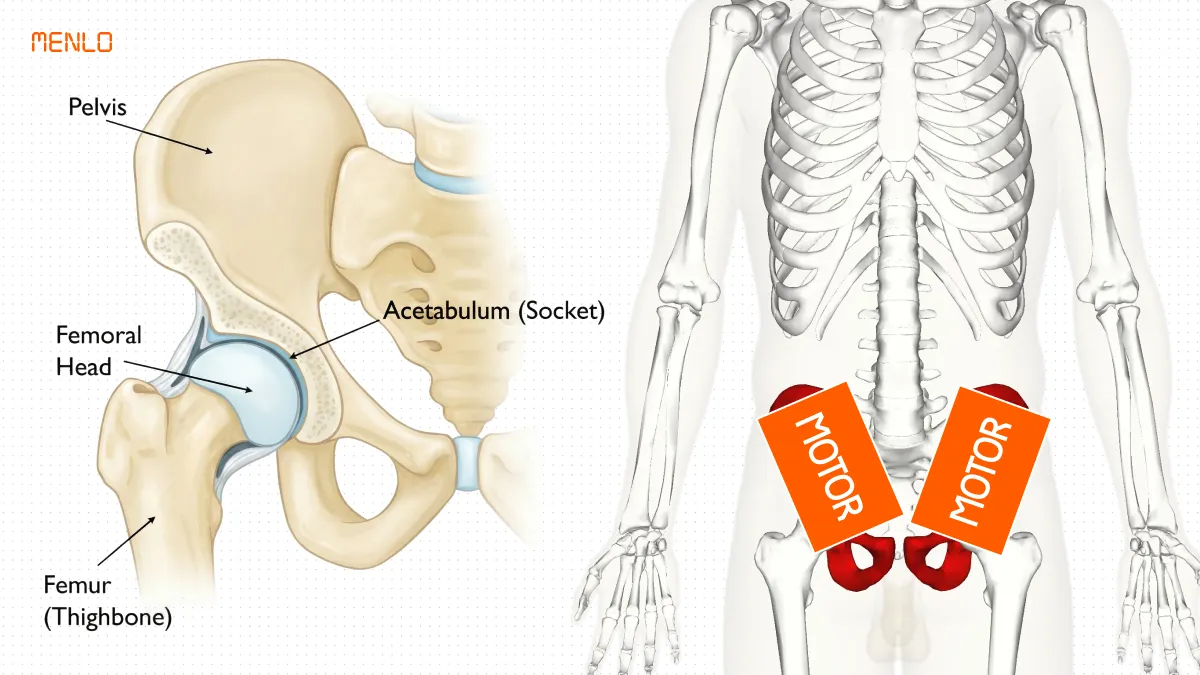

Designing for biorealism

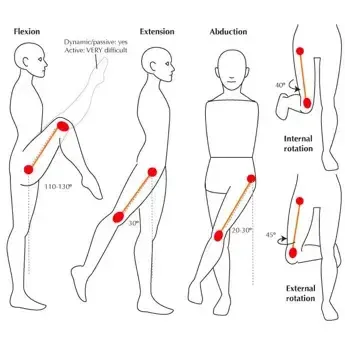

We treated human aesthetics as a functional constraint. The main constraint was the largest motor size—i.e., if a robot is undersized its joints would look too knobbly.

From there, we worked backward to determine feasible link lengths, knee geometry, and motor placement. We used human joint range targets from anatomy and biomechanics references (Basis of Human Movement) to set joint limits and identify where forces should be carried through the structure.

- The smallest we could make the robot is 1.2 meters tall.

- The final robot (whole body) will have 26 degrees of freedom (DOF) and come in under 40kg.

- We anticipate low-volume manufacturing to also come under $20,000 USD.

Leg specifications & cost

Each leg has 6 DOF to support human-like stance adjustment and foot placement. The knee is sized for approximately 40kg push capacity in demanding quasi-static cases like kneeling or hovering.

Mechanically, we packaged the leg actuators in a largely coplanar layout to simplify structure, load paths, and assembly.

The complete legs subsystem costs just over 8.5k for actuators and joint parts, the rest for batteries and control modules. We are not allowed to disclose Encos actuator pricing; you will need to get a direct quote from the Encos team.

In total, our R&D over the last 100 days came under $30,000 USD. This spend also includes a hangar, tooling, and replacing parts. This part is amortizable for the whole body and other things. Making this super feasible for other scrappy labs like ours.

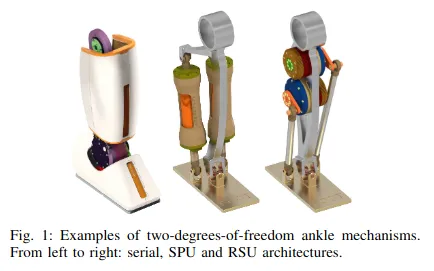

Ankles need RSU architecture

The ankles are the first to go. For humans and for robots.

Ankle design is critical because it directly determines how the foot transmits load and orientation to the ground during locomotion.

We chose a parallel RSU ankle (Revolute–Spherical–Universal) rather than a simple serial ankle with just one degree of freedom. RSU gives us two DOF ankles with both roll and pitch. Revolute actuators enable torque sharing between two motors working together to lift the whole body. This enables proximal placement of heavy components, which improves rigidity, precision, and dynamics. You also get better backdrivability characteristics, meaning the ankle can respond more naturally to ground contact forces.

Another good option would have been linear actuators. Tradeoffs: higher strength/stability, a more tendon-sinewy look, but slower speed and a slightly more expensive component.

Toes make for an adaptive foot

We added a toe joint, and yes, this was very intentional.

Similar to how human toes passively bend to conform to the ground during stance, an articulated toe increases effective contact area and helps distribute load more evenly. But the real benefit comes during the stance-to-push-off transition.

As the body moves forward, a toe rocker helps the foot roll instead of pivoting on a rigid edge. This offloads peak forces, maintains contact, and increases effective contact area. The result is more stable traction and better forward propulsion.

We implement this as an extra toe hinge joint that is articulated but not actively actuated. It’s passive and compliant. Recent analyses of Tesla Optimus, for example, suggest an articulated toe box that behaves like a hinge with passive return (spring or elastic) rather than a fully motor-driven toe. You get the benefits of toe rollover without the complexity, mass, and control burden of adding another powered joint.

What we’re improving next

We are prioritizing hip and integration upgrades based on issues discovered in full-range testing for the next iterations.

The main change is at the hip. Our initial design mounted the hip-pitch actuator at roughly 45 degrees to better distribute upper-body load through the pelvis. This packaging constraint, however, limited the achievable hip flexion and prevented a good sitting posture. We’re moving to a horizontally mounted hip-pitch motor (about 90 degrees reoriented) to recover the required range of motion and improve usability for crouch and sit motions.

In parallel, we’re tightening manufacturing and assembly quality. We missed some holes in early builds and need to improve jig and tolerance consistency. We’re also upgrading the ankle pivot components from aluminum to steel for better wear resistance and strength margins.

Finally, we’re shifting from leg-focused iteration to full-body integration. The complete assembly features 26 DOF across the whole body at under 40kg (exact mass still being finalized as we integrate components).

Want to go deeper?

We’d love your feedback. Join our Discord to contribute to our open source efforts and give us feedback.

Menlo Research is building and open sourcing an autonomous humanoid from scratch. It has a modular design, with the legs, arms, and head development happening in parallel. We build in public and share our wins (and failures, on most days) openly. You can also follow us on X , Instagram , and YouTube .

Menlo Research is working on embodied autonomy. Asimov legs enabled our Autonomy research team to start working in parallel on navigation and autonomy problems and to quickly test sim2real transfer.

Asimov is an open-source humanoid: