Noise is all you need to bridge the Sim-to-Real locomotion gap

Sim-to-Real of locomotion policies is usually framed as a physics gap traditionally in robotics. The industry responds with better contact models, friction cones, more domain randomization, etc. We benchmark simulators like Isaac Sim (PhysX) and MJX against each other (Sim2Sim) to make sure the math agrees.

Yet robots still fail in real life, in non-obvious ways.

Not because friction was 3% off, but because a CAN packet arrived late, a thread missed its deadline, or an IMU integration drifted just enough to destabilize the controller.

Reality is noisy, late, and unfair. So how do we optimize for real world uncertainty?

In our latest work on Asimov Legs, bridged Sim2Real locomotion further by running our real robot firmware and control stack inside a deliberately imperfect simulated environment.

In this post, we share the methodology and results. We are optimistic about what it implies for hardware-software-AI co-design in modern robotics.

Don’t just simulate the robot, simulate the embedded environment

The core idea is to make the processor part of the robot’s dynamics in training.

We call this Processor-in-the-Loop because the control loop closes through the actual firmware execution model. We account for its threads, timing, and numeric constraints. This makes the processor itself part of the robot’s dynamics during training.

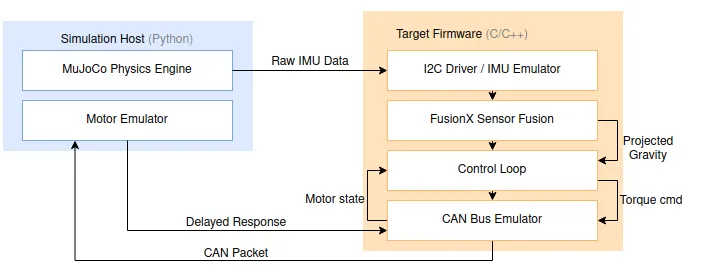

How it works:

Sensor Fidelity: We don’t cheat. We don’t pass “truth” orientation to the controller. We stream raw accelerometer and gyro data from the MuJoCo lsm6dsox model over our I2C Emulator. This mimics the exact register-level behavior of the sensor bus.

The Fusion Stack: The firmware runs the open-source xioTechnologies/Fusion C library to calculate projected gravity () in real-time. This is critical because Python math (infinite precision) and Embedded C math (constrained floats) often disagree. If our integration of the Fusion library drifts, or if the thread priority causes a bottleneck, the robot falls in real life.

Binary Confidence: We aren’t running a simplified “simulation version” of our code. The firmware talks to our CANBus Emulator exactly as it would talk to the physical CAN hardware. It doesn’t know it’s in a simulation.

The implication of this pipeline is that we catch bugs in the pull request, not when the robot is standing up.

Account for Jitters and Delays

The biggest lie in robotics is the datasheet.

Our motor datasheet claims a 0.4ms response time. In a perfect simulation, that response is instant and constant. In the real world, it fluctuates. The “jittery time” domain needs to be optimized in training.

If you train a policy with Domain Randomization (specifically, randomized actuator delays), you believe your policy is robust. But you rarely test that belief until you are on the hardware.

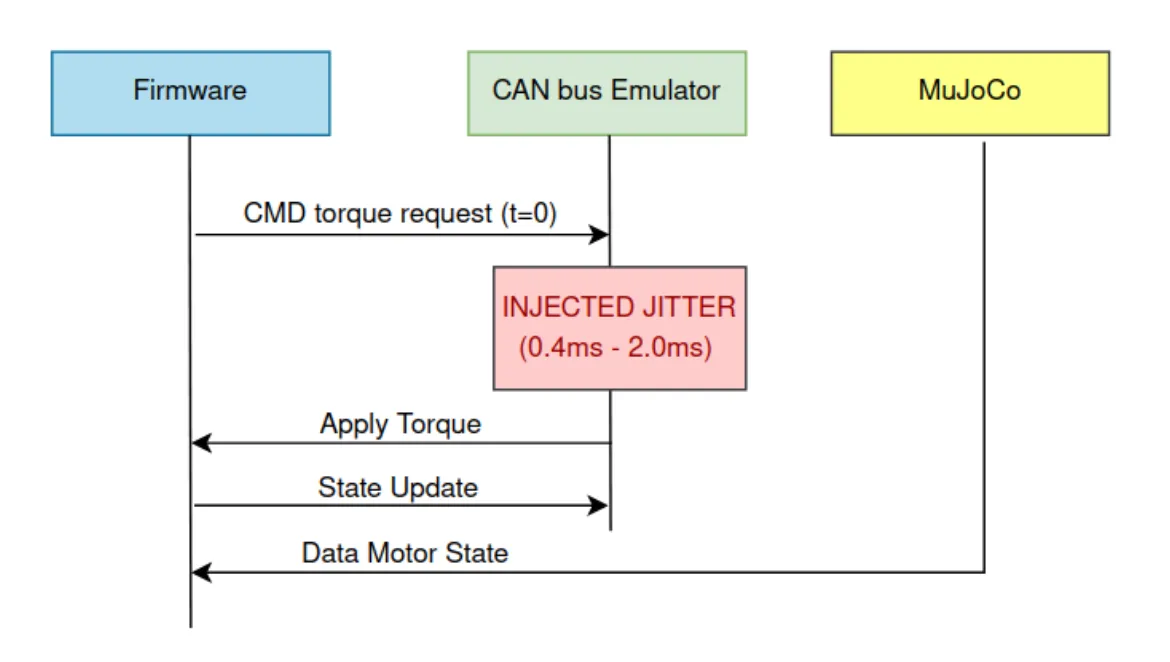

Our Motor Emulator validates this explicitly.

The emulator sits between MuJoCo and the Firmware. It intercepts the Request-Response packets and injects a random delay drawn from a uniform distribution between 0.4ms and 2ms.

This turns “Domain Randomization” from a theory into an integration test. By forcing the firmware and policy to handle this jitter in CI, we catch specific failure modes that usually only appear in the field:

- Race conditions in the threading model (e.g., what happens if the control loop finishes before the motor response arrives?).

- Protocol parsing errors in the CAN driver under load.

- Jitter intolerance in the RL policy.

- Fusion library drift due to timing mismatches between sensor reads and control ticks.

Sim-to-Real Cannot be Solved in a Black Box

Previously, when we experimented with the Unitree G1, we couldn’t achieve these results on new polices. It was banging our heads against a black box. Closed firmware hides the dominant failure modes.

Sim-to-real is fundamentally an observability problem: you can’t fix what you can’t measure.

We deploy the policy on the Asimov robot equipped with 12 Series motors. The videos below show zero-shot sim-to-real locomotion behaviors using a single trained policy: forward and backward walking, lateral walking, and balance recovery under external pushes.

Sim-to-real rollouts of a Asimov’s locomotion policy. Left-to-right: forward walking(vx=0.6m/s), backward walking(vx=0.6m/s), side walking(vy=-0.6m/s), and push recovery (from human bully).

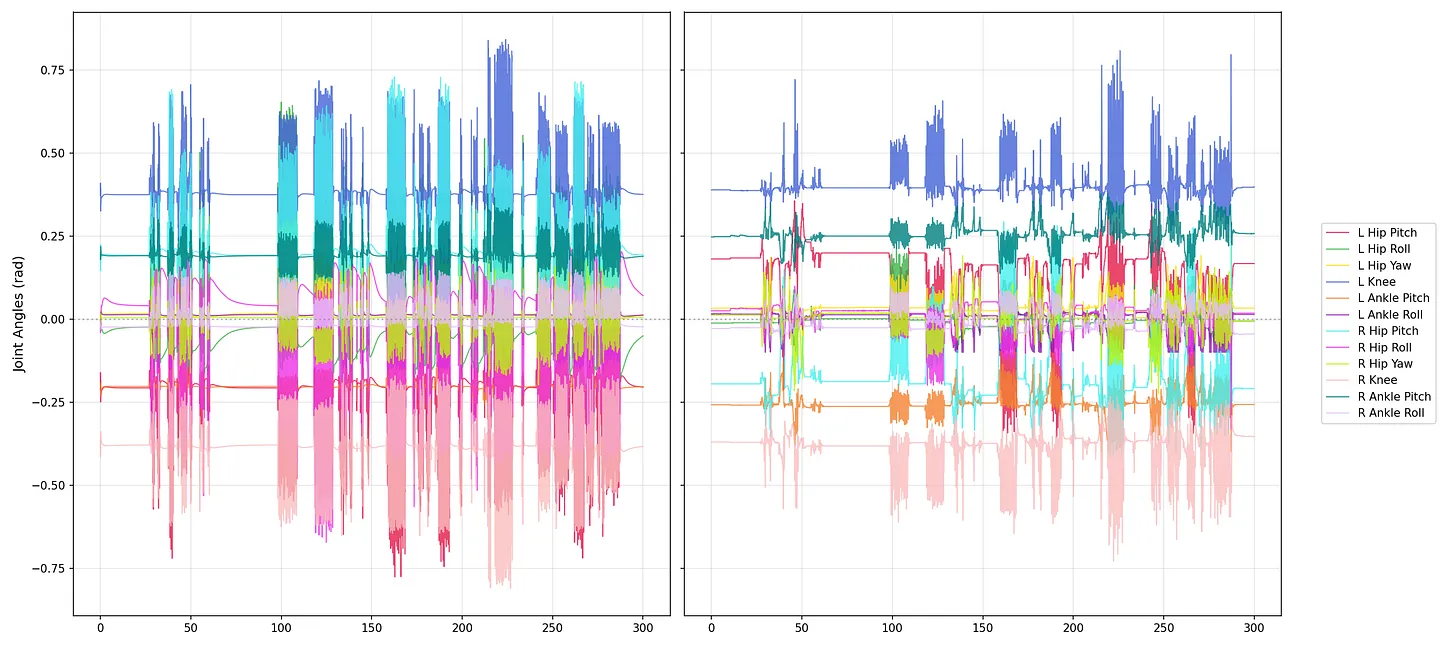

We also compared the joint position analysis graph in real(left) vs in sim(right), which let us directly check whether the policy’s motion patterns align across domains.

Co-Design is the Point

Sim2Real fails because hardware, firmware, and policy are developed in isolation, then forced to agree at the very end.

The control policy needs to experience real timing and other frequent failure modes.

Our approach works because it treats the robot as one system.

- Policies are trained assuming imperfect sensors and delayed actuators

- Hardware is designed with policy capabilities and requirements in mind

- Firmware is written to seamlessly close the gap

None of these layers are adapted later. They are designed together.

This is why we’re building Asimov as a robotic AI stack. A place where hardware, firmware, and models evolve in lockstep, and where Sim-to-Real stops being a gamble and starts being an engineering process.

The real world is chaotic and we should design every layer to survive it.

We’d love your feedback

Join our Discord here to contribute to our open source efforts and give us feedback.

Asimov is an open-source humanoid: